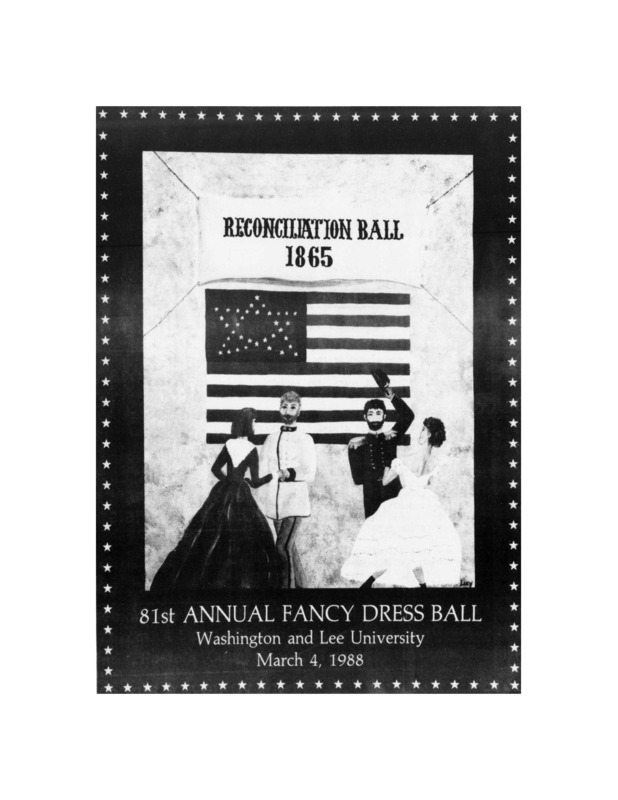

The 1988 Fancy Dress occurred on March 4, was held in the Warner Center/Doremus Gym, and was themed “Reconciliation Ball of 1865.” Tickets this year cost $45 per couple. The Glenn Miller Orchestra, Marshall Crenshaw, and INDECISION were the musical guests for this weekend. To accompany the musical talents, the venue was decorated with Civil War costumes and decor from the North and the South: buildings from NYC and Philadelphia, southern carriages, 12x18 foot American flag, blown up posters and newspapers from the Civil War, 36 Union state flags, gazebos, and a paddlewheel river-boat (Tuggle 4).

1988

Theme, Decorations, and Attire

Student Involvement

The SAB organized and executed the 1988 Fancy Dress ball; the exact number of female members during this year is unclear but the Board still appointed a male chairman. However, female members were credited for the decor. The Board encouraged costumes for the ball, but cautioned students to use “tasteful judgment” when doing so (Tuggle 4). In a Q&A with the FD chairman, Tom O’Brien, he justifies the theme chosen because of its “many possibilities and its ties to W&L history… [and] because of the possibility of bringing back the tradition of costumes” (Tuggle 17). Furthermore, after some questions had been raised about the nature and contents of the theme, O’Brien ensures readers, “we maintain that Fancy Dress is a social event and not a political one” (Tuggle 17).

Student Reaction

The 1988 Fancy Dress cycle was one of great controversy at W&L. Soon after the announcement of that year’s theme: The Reconciliation Ball of 1865, the SAB received backlash from a number of students, most notably the president of the Minority Student Association, Rosalyn D. Thompson, regarding the theme as “an insult to us all” and deemed W&L “the most racist school in the nation” (Calyx 1988 pg. 38). The chaos attracted attention from the “Virginia Associated press, The Roanoke Times and World News, state television stations, and USA Today” (Calyx 1988 38).

Various students wrote to the Phi expressing their opinions for both sides of the argument. The MSA, hurt and confused, wrote, “It’s like having a Trail of Tears party and inviting the Indians, or having a Third Reich party and inviting the Jews. What would they celebrate?” (Dunne 1). After explaining the history of 1865 and the environment African Americans were living in during that time, the MSA called for a boycott of the ball. Faculty and staff also decided to join the conversation: one faculty member publicly joined the boycott, expressing, “this appears to be a celebration of aspects of southern history that I find indefensible” (Dunne 1).

On the other hand, plenty of pro-Reconciliation Ball perspectives were depicted in the Phis. One student wrote that “Robert E. Lee holds a special place in the heart of each student here and what better way to celebrate him, our school, and the union of what was our war-torn nation tha[n] at the biggest collegiate social event in the nation; our very own Fancy Dress Ball” (pg. 4). Various letters were written to the Phi regarding the issue as well. J. Tucker Alford, class of ‘89, expressed disgust for the MSA’s “litany of whining” and called for an apology to be made to the university (Alford 2). Another student, William I. Crabill, wrote a letter addressing Thompson, asking, “Do you think that you can find a hoop skirt large enough to clothe your prejudices?” (Crabill 2). In response to the tension among the broader student body, FD chairman, O’Brien, goes on record to say that in regards to the theme and overall event, “it’s full steam ahead” (Dunne 1). O’Brien goes even further as to take a photo with a copy of the Phi featuring the story about the MSA boycott at the ball that was subsequently published in the 1988 Calyx.

Despite the overwhelmingly passionate letters against the MSA’s boycott, an alumnus, Willard Dumas, recalls his 1988 Fancy Dress experience, “I boycotted Fancy Dress one year. It was the Reconciliation Ball, but it was the Dark Continent that contributed to it. Not just black students but students who were sensitive to how black students felt said, ‘Look, we just went through this with the Dark Continent’” (Warren 201). Dumas fills in the narrative of minority students during the year of the 1987 Fancy Dress that university publications left out of their overall coverage. After the racially charged 1987 Fancy Dress, it seemed that backlash on a consecutive racially and politically charged theme was inevitable and even more so justified.

Among the commotion, the continuation of portrayals of other social pressures were included in the Phi. This year, perspectives from each year and gender were published. For example, a male and female student from each class year wrote how they felt about Fancy Dress. Most of the accounts of Fancy Dress revolve around the stigma around getting a date or Fancy Dress exceeding their own expectations. The freshmen students, having not attended a Fancy Dress weekend yet, expressed their expectations of the event.